In the eye of the storm – John Robb on Oasis’s rise, chaos, and unrivalled musical legacy

- Written by Thom Bamford

- Last updated 19 seconds ago

- City of Manchester, Music

“Read on… It’s all true,” declares Noel Gallagher on the cover of Live Forever, in a large red circle, impossible to miss. And if anyone’s qualified to tell the true story of Oasis, it’s John Robb.

A long-time friend of the band and a fixture of Manchester’s music scene, John was there from the very beginning, documenting Oasis from their early demo days to the supernova heights of Knebworth in 1996

Live Forever: The Rise, Fall and Resurrection of Oasis is the definitive deep dive into one of Britain’s most iconic bands.

Written by journalist and musician John Robb, who was embedded in the Manchester scene from the beginning, the book offers a first-hand, behind-the-scenes account of Oasis’s meteoric rise, dramatic implosion, and long-awaited return. We sat down with him to talk about the book.

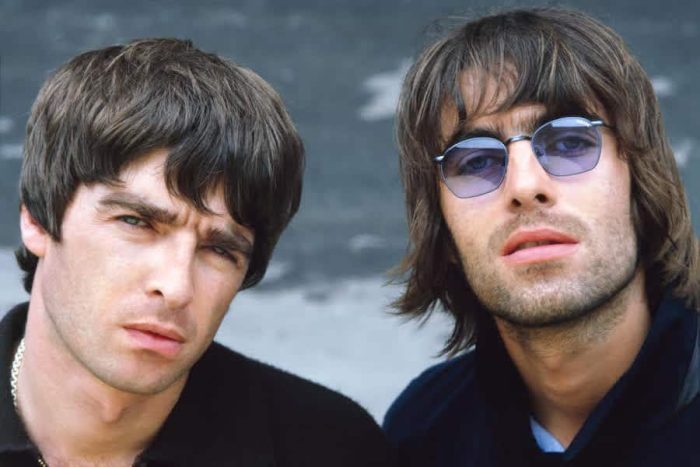

So, tell us about your first meeting with Noel and the band

I knew Noel before Oasis, before he was even in Inspiral Carpets as a Roadie, he was just a young guy I used to go to gigs with in Monton occasionally. Everyone kind of knew everyone else at that point, because the same 50 people went to all the same gigs. There were only about three venues in Manchester, too; it was a far cry from the city it is today.

Also, gigs were only on weekends! Much less stuff on than today, where you can go to a great gig every night. So you’re sort of used to seeing the same people kicking around.

And then one day it was just like, oh, he’s in a band. They used to rehearse in the Boardwalk, so we’d hear them rehearse all the time, because the band I was in was rehearsing there too.

It was a bit of a weird time. The music business had sort of considered Manchester bands as over. The London music press certainly did. The scene seemed over like nobody was ever going to make it out again. So Oasis initially were just considered like an archetype Manchester band, but they were much noisier!

They were like the Sex Pistols version of a Manchester band. When they started, like everyone, they’d be playing gigs, but nobody would be there. They were really swimming upstream against the typical music of the time. I think people think about Oasis now and just see this supersonic, meteoric rise, but they don’t realise they were grafting for two years. Nobody would have touched them with a barge pole until Alan McGee walked in and saw them play and was completely blown away by them in Glasgow.

What was the music scene like in Manchester when Oasis were starting out?

It felt a bit like guitar music had completely fallen off the radar.

Yeah, it felt like the party was over. That was the general feeling at the time. People thought Manchester had had its moment. There was this attitude, especially from London, like “Right, Manchester’s had its turn, now it’s back to business here.” London always has its bands, and there’s this strange cycle where other cities get their moment and then fade away. It’s odd when you think about it.

In Manchester itself, there was a bit of a hangover from the whole Hacienda era. Gang culture had started creeping in, and the vibe in the city had dipped. It felt a bit darker, a bit more ‘gangstery.’ So yeah, it was probably one of the low points of the last 30 or 40 years in terms of the music scene.

But that’s not to say nothing was happening. There was still good stuff going on, it didn’t all just grind to a halt. Like always with pop culture, things just went back underground. Back into rehearsal rooms, into smaller venues.

That’s what’s interesting about Oasis. It wasn’t guaranteed they’d make it. They talked the talk, and they genuinely believed in themselves, but if you looked at it on paper, their success seemed almost impossible.

What really set them apart, I think, is that maybe there wasn’t space at the time for a band like them, but because they were writing such great songs, they managed to break through. Once people heard them, it happened fast. As soon as the first single came out, “Supersonic”, everyone was on board straight away. It’s just a brilliant song.

When did you first think, wow, this band could be huge?

It felt like something was going to happen. Noel was super savvy, older, and more experienced. He knew exactly what he was doing. He’d learned a lot from working with the Inspiral Carpets.

And then you had Liam, who just had that thing. He looked cool. He was like a younger, sharper version of Ian Brown, who at the time was an icon of the Manchester scene.

The big question at the time was: where’s the audience for this kind of band? Who’s actually listening? When you write about music, you can love something, but that doesn’t mean it’s going to be big. That’s the job of the A&R people or the record labels, not the music journalists. When you’re writing, all you really think is, “This is really good.”

I think the first real inkling that Oasis might be something more came with Columbia. That was a white-label release, and people started talking; it made people realise, “Hang on, this is a lot better than we expected.” It was a limited release, so its impact was small, but it changed perceptions.

Then Supersonic came out, and everything moved quickly. They started selling out venues, not instantly, but steadily. They began building a following around the country. Radio started picking them up, the press got behind them. It felt like they were going to be more than just another cult band.

But at that point, no one imagined they’d go on to sell 20 million records. It just felt like they were going to be bigger than people expected, not necessarily the biggest band in the country.

How important were the band’s sessions in Liverpool with The Real People? It seemed like a real turning point.

Yeah, I think those sessions were massively important. Oasis spent around three months travelling over to Liverpool, where The Real People had this small four-track studio they’d bought with their advance. The Real People had sort of made it before Oasis, at least partially. I used to go over and interview them back then, before all the Oasis hype. They were very much a cult band, starting to build a bit of a following.

After The La’s, they were really the next cool thing to come out of Liverpool. Seriously talented songwriters, with an amazing gift for melody. Even now, I went to see them a few months ago and they were still brilliant, just two rough-looking lads with these unexpectedly beautiful voices. That contrast is part of their magic. They’re still writing great songs, always with strong melodies. Real craftsmen.

So yeah, I think that time was essential for Oasis. Working with a band that had already been through some of it, they picked up tricks. Like how to trim a song down, add a classic harmony, and make that harmony shine. It’s all those subtle things you pick up from being around people who’ve been doing it a bit longer. The Real People definitely brought a lot to the table.

So you were in the studio with Oasis when they were recording What’s the Story (Morning Glory). What was it like to be in the eye of that storm?

Yeah… wow. That was wild. We were actually down the road producing a band called Cable, so we caught up with Oasis in this little town in Monmouth. They invited us back to the studio, played us some of the new tracks, and it sounded fantastic.

We went over to the studio, and Oasis put some tracks on. It all sounded massive. I’ve always thought of Oasis as the last great glam rock band in a way, those big, stomping anthems. People sometimes criticise them for sounding like Slade, but what’s wrong with that? Slade was one of the great British pop bands. There’s no shame in it.

They played three or four tracks, I’m pretty sure one of them was Champagne Supernova. But then Cable got drunk and started slagging the songs off, saying they just sounded like The Beatles. Then someone played Cast No Shadow, and it all kicked off. We had to drag everyone out of there to avoid a total disaster. It was chaos. Someone threw a big bowl of pasta at someone else, and yeah, it kicked off.

So yeah, we were among the first people to hear the album. The songs sounded huge, but in that moment, it just felt like your mates’ band had made another great record. It didn’t feel historic at the time. I’m sure when people first heard the final mix of Sgt. Pepper’s in 1967, they were just thinking, “Ah yeah, the lads from Liverpool have made a really good record.”

It’s only decades later that these things become ‘historical,’ isn’t it?

Growing up listening to them, it always felt like they were destined to be this seismic force, especially after Maine Road, Knebworth, and all that.

Yeah, definitely.

But I think if you zoom out, you realise the peak had already happened. Knebworth was the pinnacle. And after that, things shifted. One of the things I explore in the book is how they evolved into a different kind of band. A really good band, still, but different. They became more of an alternative rock band in a way. People often overlook those last four albums, but I think they’re genuinely strong records.

And critics always say the same thing, don’t they? It’s all about the first album, or maybe the first album and a half. After that, it all went overblown and downhill. That’s the standard line. But when you actually go back and listen to the later records, it’s just not true.

They became quite experimental by the end. On the last album, there are drum and bass loops, backwards guitars, and it’s sonically adventurous.

They were turning rock into pop, which is exactly what the best bands do. When something slightly odd or twisted hits number one, that’s when you know a band’s ahead of the curve, just like The Beatles did in the ’60s. And Oasis were doing that too, but no one noticed. People assumed they were still the same band when, actually, they’d morphed into something far more interesting.

Like Falling Down – that one’s pretty out there.

Exactly. It’s an amazing track. If another band had made that, critics would be raving: “Wow, what a cool and unexpected twist.” It doesn’t really sound like anything else. But because people still see Oasis as the Supersonic band, which, don’t get me wrong, is a great song, they don’t realise how much they actually changed.

They evolved more than most bands ever do.

You’re one of the few people who saw Oasis from their early demos to Knebworth and everything in between. What do you think changed about the band over time? And what never did?

I think musically, they changed a lot. As we were saying earlier, they managed to evolve while staying within their own framework. They explored different directions but always remained recognisably Oasis. And really, that’s all you can ask of a band, to take what they’re good at and push the boundaries of it. They did that in so many ways.

What didn’t change? The personalities. Sure, the drummers came and went, but even that was kind of perfect. We were talking about this the other day, each drummer they had completely suited the era they were in. There wasn’t a better or worse one.

Tony was absolutely the right drummer for the first album, a proper, powerful punk rock player. Then later on, Zak Starkey and Chris Sharrock came in, more complex drummers, but perfect for the more layered, experimental stuff they were doing. Alan White, who was in the band the longest, nailed that kind of shuffle groove they leaned into during the middle period. So the drumming evolved, but always in sync with where the band was musically.

But the core, Noel and Liam, that dynamic couldn’t change. Liam’s always had that charismatic certainty, that presence. And Noel, funnily enough, is quite introverted. On stage, he’s head down, focused on his guitar. Neither of them ever did the whole “hands in the air, ‘Hello Wembley!’” thing. Even in America, which completely baffled audiences, there was zero showbiz about them. And that’s still the case.

We have to touch on the Gallagher dynamic. The whole Cain and Abel with guitars. Knowing them both, do you think they ever truly understood how much they needed each other? And do you think they’d ever admit it?

Great question. And… I’m not sure they ever fully understood it in the moment. Or if they did, I don’t think they could bring themselves to admit it. That push and pull between them, that tension, was such a huge part of what made Oasis what it was. Noel needed Liam’s raw, instinctive energy just as much as Liam needed Noel’s songwriting and direction.

But they’re both so proud, so wrapped up in their own identities, that I don’t think they could ever say it out loud. Maybe privately, maybe in moments, but publicly? Probably not. Still, I think deep down they know. You don’t create something that monumental without knowing what the other brought to the table.

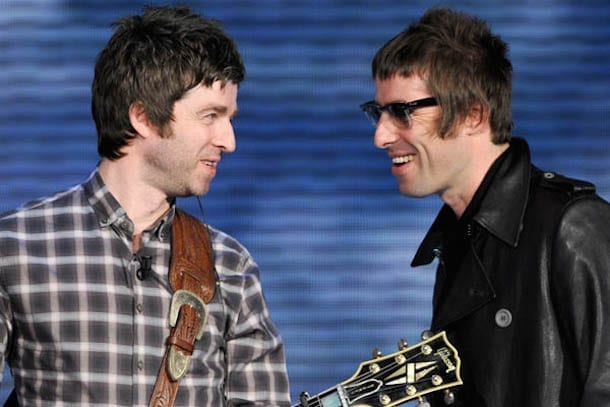

I don’t think they argued all the time. The rows they did have were so spectacular and often public that they became the dominant narrative. But I think there were long stretches where they got on just fine.

When you look at their history, they shared a bedroom from the moment Liam was born, growing up in that tiny semi in Burnage. Then, not long after that, they went on the road and spent the next 16 years sharing buses, hotel rooms, stages… they were never really apart. And when you consider that, it’s incredible how long they kept it going.

People often say they put out a couple of albums and then self-destructed, but in reality, 16 years is a long career for any band, especially one with that much pressure and attention. I think there was a deep mutual respect there. But, being from Manchester, they were never going to come out and say something like, “I think you’re amazing.” That’s just not how it works round here, is it?

There were these really revealing little moments, though, like when Noel would give Liam the lyrics to a song and sing him the melody, and Liam would just walk straight into the booth and nail it in one or two takes. Morris, the producer, once said he’d never seen anything like it. Usually, getting a good vocal down takes ages, loads of takes, chopping things together. But with Liam, it was basically two takes, and he was off to the pub.

Someone asked him once, “How do you do that?” And he said, “These songs are in me as well.” And I think that’s really telling. Sure, Noel was the one writing them, but they were coming from both of them, really. They shared something deep, something instinctive. It’s the kind of closeness people don’t talk about, or even fully understand, but it was there.

Of course, when they did clash, the fallout was massive. Bigger than with most bands. But the difference was, they’d have a huge fight, and then two weeks later they’d be back in the studio, getting on with it. Most bands wouldn’t survive that kind of tension.

Yeah, totally. I’ve always loved Wibbling Rivalry, it gets a bit mad in places, but it’s hilarious.

That’s a classic, isn’t it? So early, too, that was before they’d even really made it. It was from the first tour.

Do you think we’ll ever see another great working-class British band like Oasis again?

I think you’ve always got to say: never say never. It’s definitely harder now. But it was hard back then, too, even when they were starting out. Things were already beginning to change, you needed a lot more than just a great band. You needed the right connections, backing, and a label on your side. Noel had a link through working with Inspiral Carpets, sure, but even then, the London music press had already set the scene with Britpop, with Blur front and centre, and like Noel says in the book, when Oasis turned up, it was like London never forgave them. It’s still like that now, just on steroids.

You do still get these bands, a group of lads from Rotherham or Wigan, and they’re out there making great records. They’re releasing albums, even hitting the charts, but you won’t hear them on the radio or read about them anywhere mainstream.

The internet’s helped, though. It’s opened up space for bands that are savvy, and for fans who are incredibly supportive. They carve out their own music worlds now. Like, how did The Reytons manage to get two number-one albums last year? That’s the perfect example. You’ll never hear them on 6 Music, but they’ve built something strong without needing the traditional system. So yeah, it is possible.

Reaching Oasis’s level, though? That’s something else. That’s once in a generation. One of their albums sold 24 million copies. That’s not normal. That’s cultural impact on a whole different scale.

How was the experience of pulling this all together for you? Looking back over thirty(ish) years. It must have felt like a real trip down memory lane.

It definitely was. I’d say every period is exciting in its own way. In 20 years, people will look back on this period and say, “Wow, must’ve been amazing to be around then.”

We always forget Tuesdays and Wednesdays, don’t we? We only remember the Saturdays.

But yeah, it was good going back to that time. Places like New Mount Street… I was thinking about it all again and reconnecting with people I hadn’t spoken to for 30 years, people who are still around town, but you just don’t see them. It was good to dust off those old stories and try to recreate the feel of those places, what they were really like. There’s definitely an element of nostalgia in there. It took me back to a different time in life, before everything really happened, before things got big.

I was working in-house then, going to kitchen parties in Hulme, hanging out at New Mount Street. Back then, it felt really out of town, just a warehouse on the edge of things. I went back there a few weeks ago for a meeting, just across the road, in what used to be a pub. It’s not a pub anymore, it’s offices now. And New Mount Street itself is all flats. It’s practically in the city centre now. Shows how much Manchester’s changed.

It’s a completely different world. But the one we’re in now, the whole rise of the city centre, I’d argue that pop music helped build that. The success of Factory, The Smiths, Oasis… all of that made Manchester bigger, more confident. It turned the city into a place people wanted to live in.

What was it like interviewing Noel at Sifters recently? He seemed… unusually warm and kind, especially when talking about Liam. Were you surprised by how open he was?

Yeah, it was surprising. I’d thought going in that it might be good to try and steer things in a different direction, something beyond the usual back-and-forth drama. That stuff’s funny, entertaining, sure, but I was hoping for something more reflective. I didn’t expect him to go that far with it, though.

It really was a different side of him. That interview was recorded about three months before it aired, so it’s hard to pinpoint exactly when the reunion talks really began. I think venues were getting booked as far back as January, maybe even before the band had officially decided anything. So who knows, maybe they’d already made up their minds, maybe not. It could’ve happened any time between that interview and the announcement.

Anything else the readers should know before buying your book?

What I’ve tried to do, beyond just telling the story, is to humanise it. To put it in context. To show what else was happening in the wider music scene at the time, so it’s not just Oasis in isolation.

There’s this brilliant irony when you look back at the first Britpop cover story in Select magazine. Neither Blur nor Oasis were in that piece. Oasis weren’t known yet, they were just another band in a rehearsal room. Blur had already put out two albums, but weren’t even being framed as “Britpop.” So the whole “Battle of Britpop” ended up being between two bands that weren’t even considered part of it to begin with, and neither of them would’ve called themselves that, either. It’s a wonderfully pop culture twist, isn’t it?

You can get a copy of Live Forever: The Rise, Fall and Resurrection of Oasis by John Robb, by clicking here

- This article was last updated 19 seconds ago.

- It was first published on 10 June 2025 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: [email protected]

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to [email protected]

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: [email protected]

Two Manchester restaurants named in National Restaurant Awards top 100

Remembering the inspiring life of the activist who transformed LGBTQ+ rights in the UK